|

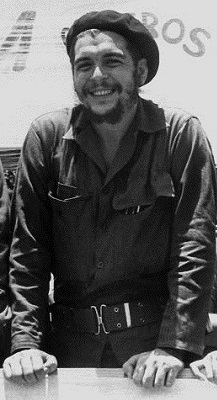

~ Ernesto Che Guevara

~ Galéria

~ Oldal

~ Bejelentkezés

~ Vissza a Főoldalra

Ernesto Che Guevara, az argentin származású forradalmár, miniszter, gerillavezér és író, Buenos Aires-ben szerzett orvosi diplomát, majd a kubai forradalom során jelentős szerepet játszott a szigetország felszabadításában és újjáépítésében. A kubai gazdaság talpraállításáért dolgozott, küzdött az oktatás és az egészségügy fejlesztéséért, az írástudatlanság és a faji előítéletek felszámolásáért. Saját példájával népszerűsítette az önkéntes munkát. Kongóban és Bolíviában is harcolt - harminckilenc éves volt, amikor az amerikai-bolíviai csapatok csapdába ejtették és kivégezték.

| | |

|

| | |

|

|

|

Et Tu, Fidel? The Alleged Betrayal of Ernesto “Che” Guevara

“No contact with Manila,” Ernesto “Che” Guevara wrote several times in his diary as he marched to his death in Bolivia and, behind the phrase, is Cuban leader Fidel Castro’s betrayal and abandonment of the legendary guerrilla fighter, Cuban journalist Alberto Müller said.

“Manila” was the codeword for Cuba, Müller told Efe in an interview ahead of the presentation at the Buenos Aires International Book Fair of his book “Che Guevara. Valgo más vivo que muerto.”

The title comes from a phrase attributed to Che when he was found in the Bolivian village of La Higuera and contrasts the guerrilla’s desire to live with Castro’s order to avoid being captured alive, highlighting the “great differences” existing in 1967 between the two revolutionaries, Müller said.

Müller said there was a guerrilla unit in Havana ready to deploy and rescue Guevara, but “Fidel never authorized the mission,” abandoning the guerrilla leader to his fate.

Che was shot dead on Oct. 9, 1967, in La Higuera.

“He died in a pitiful manner. Without medications for his asthma, without boots and only rags wrapped around his feet, without water, without food and without allies,” Müller said.

To understand why Castro withdrew his support from Guevara, the author takes the reader back to what he considers a turning point in the relationship between them, the 1965 Afro-Asian Conference in Algiers.

Guevara’s address to the assembly meant “a break up with the Soviet Union that harmed Che’s relationship with Fidel,” the author said.

Guevara criticized Moscow, accusing the USSR, without mentioning it by name, of being “accomplices of U.S. imperialist exploitation,” just when the Cuban leader was about to conclude agreements on military cooperation with the Kremlin.

The estrangement between Guevara and Castro increased over time, and deepened when the Cuban leader, without consulting the Argentine-born guerrilla, decided to withdraw Cuban fighters from the Congo, leading to the mission in Bolivia that Müller describes as an “induced suicide.”

“Why Bolivia?” Müller would ask Castro if he were to interview him.

“Che’s posture ran against Fidel’s interests,” the author said. “Che became a pest, an inconvenience for the Cuban Revolution, a pebble in the shoe.”

Müller said several historians and Che biographers that helped in his research agreed with him that “Guevara wanted to go to Argentina, his homeland, to liberate it, and in Havana they invented the Bolivia campaign for him.”

The author said he found out that two years before Guevara’s final mission, Castro had acknowledged that Bolivia “didn’t have conditions for a guerrilla movement” and the peasants there did not need a revolution because agrarian reform in the 1950s had given them ownership of the land.

Even so, the Cuban leader sent Guevara to Bolivia and months later cut off the link with supporters in La Paz, increasing the guerrillas’ isolation and worsening their situation.

“I think Che must have died being very aware of his betrayal,” Müller said. EFE

[source]

| 2015.05.22. 22:02, Aleida |

Human side of revolutionary Che Guevara

La Higuera, Bolivia - A seven-hour drive from Santa Cruz — a city in eastern Bolivia — on a dusty mountain road took me to La Higuera, a village 2 000 meters above sea level.

About a dozen shanties built along the road were the homes of its 80 or so inhabitants. It was here 47 years ago that Ernesto “Che” Guevara, a guerrilla revolutionary committed to the goal of liberating Latin America, was captured by the government army and executed. After strolling through a symphony of birdsong to the centre of the village, I found a bust of Guevara on a pedestal. His strong eyes seemed to show determination.

Guevara was born to a wealthy family in Argentina. After meeting former Cuban President Fidel Castro in Mexico, he went to Cuba and helped lead the guerrilla war there. On the heels of the success of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, he was appointed the president of the National Bank and the minister of industry. He left Cuba in 1965 for Congo and sneaked into Bolivia after leaving Congo.

Guevara was executed by a firing squad. His body, which the military had secretly buried, was discovered in 1997. The school where he was executed has been transformed into a memorial hall that local residents take turns managing. The list of names signed in the guestbook shows that tourists from all over the world have visited the village, walking in Guevara's footsteps.

“The village residents, who believed the government when it called the guerrillas 'murderers,' did not try to help Guevara when he was captured. And they all regretted it when they learned afterward that he had dedicated his life to the liberation of Bolivia,” said Sabina Chuki, a 38-year-old farmer.

Chuki said he has heard his elders repeat words of remorse countless times since his childhood. Guevara's popularity still continues in the village, which is located in a poor area where many live on less than a dollar a day.

Juanita Castro, the younger sister of former Cuban President Fidel Castro, describes Guevara as “an inhuman, cold fish” in her memoir “Fidel y Raul, mis hermanos” (Fidel and Raul, my brothers).

However, Julia Cortez, a 66-year-old housewife who came into contact with Guevara just before he was shot, remembers him differently. “He was a humble, polite person,” she said. Cortez, who was 19 at the time, had been working at the school where Guevara was executed. On Oct. 9, 1967, just before he was killed, she brought him some peanut soup that her mother had made. He must have been famished, Cortez recalls, as he took the bowl with both of his hands - which were tied together - and drank the soup down in one gulp. He told her, “This soup is worth more than gold. Thank you. Thank you so much.”

As Cortez left the classroom with the empty bowl, Guevara pushed open the door with his elbow and smiled at her as she looked back.

“He had gentle eyes for somebody who was prepared to die,” she remembers. “His last smile is still engraved in my mind.” Not long after that, the sound of gunfire echoed through the village.

Source

| 2014.11.07. 17:49, Aleida |

Hasta siempre, Comandante! Che Guevara’s ideas flourish decades on

Che Guevera died 47 years ago, but he continues to inspire millions around the world. The popularity he enjoys so many years after his death is proof that though “they” may have killed the man, “they” will never extinguish the ideas for which he died.

On 9 October 1967, Ernesto “Che” Guevara was executed by a Bolivian army officer at the end of his ill-fated attempt to foment revolution throughout Latin America. He was executed at the behest of the CIA, who hoped his death would deal a shattering blow to the influence of the Cuban Revolution in a part of the world traditionally viewed as America's backyard; its role to provide the cheap labor, raw materials, and markets required to maintain the huge profits of US corporations.

But the CIA were wrong, just as successive US administrations have been wrong, in thinking that the ideas for which Che Guevara fought and died could ever be ended with a bullet. On the contrary, over four decades on from his death the Cuban Revolution continues as a beacon of inspiration and hope to the poor of the undeveloped world.

That a tiny island nation with a population of just over 11 million people, located 90 miles off the coast of Florida, should have the temerity to assert its right to political and economic independence from the United States and survive for so long is nothing short of immense. Indeed, many believe that not only have the ideas for which Che Guevara gave his life survived, they have never been more potent, illustrated by the left turn taken throughout the region in recent years. It is a political turn responsible for transforming a part of the world traditionally associated with military juntas, right wing autocracies, and US puppet regimes into the very opposite.

Today Latin America is a part of the world where democracy has taken root, where the tenets of the Washington neoliberal consensus have been rejected in favor of social and economic justice as the objective of government.

Undeniably, Che's legend has not only continued unabated since his death it has grown. In every town and every city, from Los Angeles to London, Beirut to Bethlehem, from Nairobi to New Delhi, the iconic image of him carrying that expression of burning defiance, captured by Alberto Korda in 1960, is as ubiquitous as it is powerful, found on everything from T-shirts to coffee mugs, rugs, posters and a myriad other items. For many it represents something transcendent in the human experience, an idea that stands in opposition to the values of individualism and materialism which are drummed into us every minute of every day in the West.

A read through Che's writings brings home the fierce determination of a man who burned with anger at the injustice, oppression and exploitation suffered by the world's poor. In his address to the United Nations General Assembly in1964, he said:

“All free men of the world must be prepared to avenge the crime of the Congo. Perhaps many of those soldiers, who were turned into sub-humans by imperialist machinery, believe in good faith that they are defending the rights of a superior race. In this assembly, however, those peoples whose skins are darkened by a different sun, colored by different pigments, constitute the majority. And they fully and clearly understand that the difference between men does not lie in the color of their skin, but in the forms of ownership of the means of production, in the relations of production.”

Not satisfied with merely delivering such a powerful affirmation of solidarity with the poor and oppressed of another land, Che embarked for the Congo in an attempt to give meaning to them, in the process abandoning the relative comfort and status earned him by the success of the Cuban Revolution to risk his life in a mission to spread the revolution throughout the developing world.

In a later speech to the Afro-Asian Conference in February 1965, he offered this admonition:

“There are no borders in this struggle to the death. We cannot be indifferent to what happens anywhere in the world, because a victory by any country over imperialism is our victory, just as any country's defeat is a defeat for all of us.”

For Che Guevara the struggle against imperialism and exploitation could only be won gun in hand, utilizing in his view the same kind of violence used without compunction by the oppressor. Not for him non-violence and peaceful protest. His experience, his observation of the poverty and truncated lives suffered by millions throughout Latin America and Africa instilled in him a rage and a desire to visit retribution on the system he considered responsible.

In this he was very much a product of his time, when people of the developing world were locked out of the democratic process in parts of the world where right-wing dictatorships made recourse to violence inevitable.

Despite the myriad articles, analysis, and commentary produced on Che Guevara and his life, much of it hostile and withering, one incident sums up more than any article ever could the enduring force of the Cuban Revolution whose ideas he died trying to spread.

In 2006 Mario Teran, an old man living in Bolivia, was treated by Cuban doctors volunteering their services free of charge to Bolivia's poor, just as they have and do to the poor in every corner of the developing world in medical missions that have transformed the lives of millions. They performed an operation to remove cataracts from Mario's eyes, which succeeded in restoring his sight.

Mario Teran is not just any old man, however. He is the Bolivian army officer who executed Ernesto “Che” Guevara in 1967.

[Source]

| 2014.10.10. 11:55, Aleida |

Pontosan 47 éve végezték ki Che Guevarát

Minden bizonnyal lehetetlen egy élet történetét egy újságcikk hasábjaira zsugorítani, a feladat pedig csak nehezebbé válik, ha egy olyan személy kalandjait, próbáljuk összegezni, aki kétség kívül Latin-Amerika kortárs történelmének legvitatottabb eseményeinek volt szemtanúja, sőt cselekvő részese.

A következőkben a Corriere della Sera olasz napilap Dariel Alarcón Ramírezzel, azaz "Benignóval", Ernesto Che Guevara egykori harcostársával készített interjút olvashatják, amely új megvilágításba helyezi a Guevara halálához vezető történéseket.

Az egykori gerilla, Daniel Alarcón Ramírez, fedőnevén "Benigno" 1996-ban emigrált Kubából Párzsiba, miután elmondása szerint "kiábrándult" a kubai rendszerből és elvesztette a forradalom ügyébe vetett hitét.

Benigno egyenesen azzal gyanúsította Fidel Castrót, hogy Moszkva parancsára 1967-ben elárulta a Bolíviában maroknyi gerillát irányító Guevarát, akit Brezsnyev "rendkívül veszélyes elemnek" titulált. Guevara egykori társa arra is rávilágít, hogy Che haláláért közvetlenül Moszkva és Fidel voltak felelősek, mivel a Bolíviai Kommunista Párt Havanna és Moszkva nyomására vonta meg létfontosságú támogatását a Santa Cruzban harcoló felkelőktől.

1967-ben Benigno egyike volt annak a három gerillának, akik túlélték a kubaiak bolíviai kalandját és Chilén keresztül visszajutottak a szigetországba.

"A szovjetek veszélyes elemként tekintettek Guevarára, mivel Che nem támogatta Moszkva "imperialista" terveit. Fidel - látván, hogy Kuba túlélése a szovjetek gazdasági segítségétől függött - egyszerű államérdekből beadta a derekát és megszabadult egykori harcostársától. Az sem elhanyagolható tény, hogy akárcsak Cienfuegos, Che Guevara is sokkal népszerűbb személyiség volt Kubában, mint Fidel" - mondja Benigno.

"Mi a forradalmat akartuk exportálni, de magunkra hagytak Bolíviában. Ezt Guevara is tudta, és biztos vagyok benne, hogy semmi kétsége sem volt a felől, hogy a biztos halálba tart a bolíviai őserdőben" - folytatja Benigno, aki 17 még évesen Kubában csatlakozott a "szakállasokhoz", miután Batista katonái megölték a 8 hónapos terhes feleségét, Noemit.

Az egykori forradalmár, akinek bár lövése sem volt a szocializmusról, elmondása szerint a Sierra Maestrában mindenkinél jobban kezelte a fegyvert. Az ideológiába Che vezette be: "mindent tőle tanultam, elvégre egy analfabéta földműves voltam".

"Nem volt egyszerű elnyerni Guevara bizalmát, de tény, hogy becsületes ember volt. Ő volt az egyetlen kubai vezető, aki saját pénzéből fizette a szolgálati gépkocsiját" - emlékezik Benigno néhány apró részletre.

A most hetven éves gerilla szerint Cienfuegos és Guevara népszerűsége háttérbe szorította a Castro testvéreket, amely feszültségeket szült a kubai forradalom vezetői között.

"Cienfuegos egy rejtélyes repülőgép balesetben halt meg - sohasem derült ki, hogy mi is történt pontosan, és arra is emlékszem, amikor Kongóban Guevarával hallgattuk a rádióban, amint Fidel felolvasott egy levelet, amelyben Che lemondott minden tisztségéről és kubai állampolgárságáról." - mondja Benigno, aki szerint a hír hallatán Guevara magánkívül rugdosni kezdte a rádiót miközben így kiabált: "nézzétek hova vezet a személyi kultusz!".

Amikor a balul sikerült kongói küldetés után a kubaiak visszatértek Havannába, Fidel ajánlatára vágtak bele a bolíviai gerillacsoport megszervezésébe, mivel a pártvezetés szerint az országban forradalmárok hadoszlopai vártak bevetésre. Amikor Che és csapata megérkezett Bolívába, gyökeresen más volt a helyzet a terepen.

"A Bolíviai Kommunista Párt - talán Moszkva parancsára - megvonta tőlünk minden támogatását, a beígért erősítéseket nem kaptuk meg, és a titkos ügynökök hálózata is mese volt csupán. Voltak titkos ügynökök, csak azok nem nekünk dolgoztak" - meséli Benigno.

"Miután bekerítettek minket Guevarát elkapták, és később tudtuk meg, hogy kivégezték. Mi hárman - Pombo, Urbano és én - Chilébe menekültünk és Salvador Allende kormányának segítségével tértünk vissza Kubába."-tette hozzá.

Később Benigno, egy ideig Occidente tartományának börtönparancsnokaként tevékenykedett, amely poszton, a köztörvényes rabok és politikai foglyok lesújtó körülményeit látva végleg kiábrándult a kubai rendszerből, és mint elmondta közel harminc éven keresztül "kettős életet élt" egészen 1996-ig, amikor végül Párizsba emigrált, ahol Fidel Castro kormányát keményen kritizáló könyvet adott ki.

Che Guevara korabeli és mai politikai megítélése egyaránt ellentmondásos. Rajongói a humanista forradalmárt látják benne, erkölcsi szigorát, az emberi méltóság és szabadság iránti elkötelezettségét méltatják,[2] baloldali bírálói forrófejű politikai kalandornak, jobboldali ellenfelei hidegvérű tömeggyilkosnak tekintik. Dél-Amerikában sokan egyfajta apokrif szentként tisztelik.

| 2014.10.10. 11:52, Aleida |

| | |

|

|

|

~ Ernesto Che Guevara

~ Gallery

~ Site

~ Log in

~ Back to the Main page

Ernesto Che Guevara, the Argentine-born revolutionary, minister, guerrilla leader and writer, received his medical degree in Buenos Aires, then played an essential part in the Cuban Revolution in liberating and rebuilding the country. He did his best to set up the Cuban economy, fought for the improvement of the education and the health system, the elimination of illiteracy and racial prejudice. He promoted voluntary work by his own example. He fought in the Congo and in Bolivia - he was thirty-nine years old, when he was trapped and executed by the joint American-Bolivian forces.

| | |

|

|